Completed on 27 August 2016, screenprinting and drawing on birch cradled panel (centre) and 20 gauge sheet steel (also includes acid etching and sandblasting) on the two end

panels. The steel is subsequently bonded to birch cradled panels. Each

panel is developed individually and the three components are fastened

together when complete. Dimensions are 49" long x 17" wide and 3/4" deep

(approx 125cm x 43cm x 2cm).

Completed on 27 August 2016, screenprinting and drawing on birch cradled panel (centre) and 20 gauge sheet steel (also includes acid etching and sandblasting) on the two end

panels. The steel is subsequently bonded to birch cradled panels. Each

panel is developed individually and the three components are fastened

together when complete. Dimensions are 49" long x 17" wide and 3/4" deep

(approx 125cm x 43cm x 2cm). A visitor who 'comes from away' may become vaguely aware, while traveling in rural Newfoundland, of a growing uneasiness, generated perhaps by the vast bog-soaked rock-strewn barrenness of much of the landscape ('The Barrens') often fading into the mist horizontally and vertically, interspersed with claustrophobic passages of impenetrable scrubby bush ('tuckamore') beneath heavy dripping skies. Add to this all major roads displaying signage about moose/vehicle incidents, the dangers of which are amplified by the very apparent lack of other travelers, between sudden complete immersions into frequent banks of rolling fog. That's when the weather is nice; it can get much worse (and also much better!). The uneasiness may become identified with the sense that one is passing through an utterly different but also utterly indifferent place, where nothing is even remotely familiar or certain, including arrival at one's intended destination; in fact, the occasional sudden appearance of normality is so unusual that it could be mistaken for a dream. As in Irish mythology about the daoine sidhe, is it possible that you've not really driven or walked for a day at all, you've actually just spent an hour with the fairies because this perfectly normal gas station where you seem to have resurfaced out of a fog bank has a calendar inside dated 1954? It is an experience of constantly being on a threshold of certain uncertainty, moving in an amorphous space between points on a map with names like Cow Head and Blow Me Down, wandering in a kind of perpetual boundary zone which seems to epitomize The Uncanny, all surrounded by an ocean that pounds relentlessly at the shores and cliffs. Well, welcome to Newfoundland! The strangest thing is once you get used to it, you won't want to leave...and it may very well turn out that you weren't who you thought you were when you arrived, either.

|

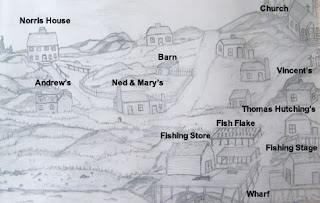

| The Random Passage site, drawing by Linda Bannister |

|

| The Random Passage Site, near Bonaventure, Newfoundland |

Like the old boys used to say

All you want The Rock for is sleeping

You spend your day out in boat

And you sleep on The Rock.

|

| Random Passage family home |

|

| Daybed in a cottage in Heart's Delight |

Survival over the winter depended on the quantity and quality of cod caught and processed during the summer, which determined how much credit the families might be able to claim at the fish merchant's store to buy food basics for the winter and the gear necessary to start fishing the next year. Archived documents of the English fish merchants record in one word the fates of those who failed to meet their fish quotas: 'starve'. We often associate the word 'plantation' with the history of slavery in the New World. The plantations established in Newfoundland - and they were called plantations by their English owners - for the purposes of fishing cod were just as much establishments of slave labour as any European plantation along the Eastern seaboard down to the Caribbean and Central and South America. The exact living conditions of the poverty-ridden outport fisher folk are only beginning to be studied within the larger picture of English-Irish conflict, 'plantation' strategies and politics in the 16th to 19th Centuries, a picture which, conveniently for the English colonizers, barely survives today on the Newfoundland landscape, yet continues to have profound effects on the social and economic lives of outport descendants. And so the appearance of the Random Passage Site, an artificial albeit historically accurate construct, speaks to the English-Irish outport history of Newfoundland and Labrador, a journey for the Irish as it were from one form of disappearance and dispossession to another. Like the massive icebergs drifting offshore, sublimely indifferent to the 25,000 years they represent, much of that history will remain out of sight, destined to disappear into the fog or the sea and time itself.

|

| Galway hooker, Dingle, Ireland |

Inscribed but barely legible in the ink of the central panel is a quote by an Aran islander from John Millington Synge's The Aran Islands:

'...A man who is not afraid of the sea will soon be drownded, for he will be going out on a day he shouldn't. But we do be afraid of the sea, and we do only be drownded now and again...'.

Seventy years later, Candace Cochrane published the following quote from a bayman in her superb book Outport -The Soul of Newfoundland (also the poem above called Out in Boat):

'...A small boat will never swamp you if it's handled right. I've been out in seas that you'd never believe any small boat could ever live in. You see waves where you have to look straight up at them. If you keep going and head right into them, you're going to get it, but the whole ocean's not breaking like that, eh? You see a wave coming aways off, cut off, cut off, cut off, and tip over the corner of it. You got to understand the sea...'

Sources quoted::

Cochrane, Candace Outport - The Soul of Newfoundland Flanker Press Ltd, St. John's NL 2008

Synge, John Millington The Aran Islands with drawings by Jack Butler Yeats (1907) edition 2008 Serif London

Additional Reading:

McCann, Phillip Island In An Empire - Education, Religion, and Social Life in Newfoundland, 1800 -1855 Boulder Publications, Portugal Cove-St. Philips, Newfoundland and Labrador (2016)

Morgan, Bernice Random Passage Breakwater Books Ltd, St. John's NL 1992

* probably from the Dutch schoon meaning 'clean' and/or 'beautiful', closely related in the sense of the phrase schoon schip maken which means 'to come clean', but which translates literally as 'to make a clean ship', hence schooner. Or at least that's my best guess!